Winter tires slide on ice. A pickup rolls past a stop sign, colliding with traffic laws before disappearing safely into suburbia.

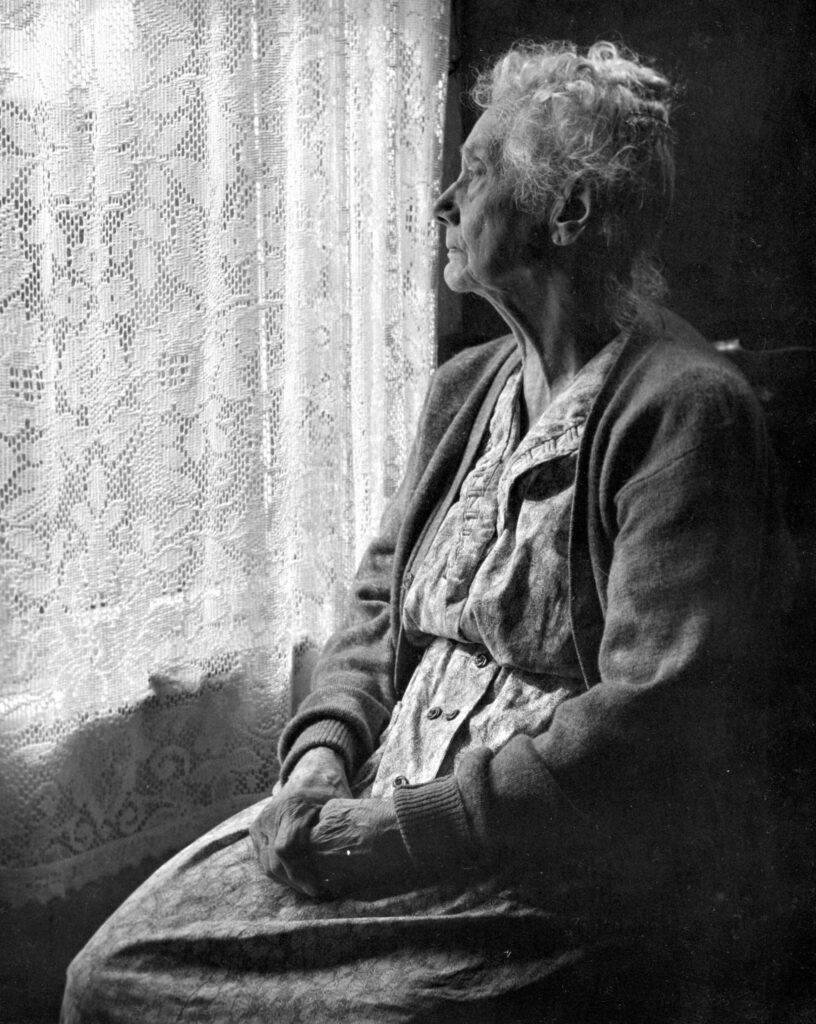

“Eleven-zero.” Mrs. Meyers frowns out her sitting room window, pencils a tally mark in her notebook. Reclined in her armchair like a toddler restrained in a car seat, she waits, tongue tut-tutting against the roof of her mouth between sips of steaming peppermint tea. She leans forward, palms to knees, hearing joints creak, and pulls a bag of soggy peas from the middle of her back, leaving a wet patch. It lands on the carpet and seeps in. Nancy will clean it next time she visits.

A minivan slows as it passes the stop sign, sprays slush as it goes.

“Twelve-zero.” Mrs. Meyers adds to her tally. “And to think there are children on board!” She says it into her tea, then exchanges the mug for the portable phone on the end table and dials.

“Hi, you’ve reached Nancy! I’m probably working right now, so leave a message at the—” BEEP.

Mrs. Meyers packs her cloth grocery bags into the back of her Civic, throws her purse on the seat, and slides her cane between the driver’s door and driver’s seat. Right hand straining to reach the passenger’s headrest, left on the wheel, she reverses down the driveway with care. Tires crunch against salt, the engine revs. And revs. And revs. Tires spin.

Mr. Nesbitt watches from his bedroom window across the street as she reverses into the snowbank at an angle, tires without grip, rotating aimlessly. He spies her through the rear windshield, in a staring contest with the immovable pile of snow. Her eyebrows are furrowed and Mr. Nesbitt thinks she looks like she’s in a battle of wits with the snowbank. Eventually, she pulls back into the driveway, the door flies open, and she totters, three-legged, back into the house, purse left on the seat.

Later, when Nancy asks her if she needs groceries, she says she already bought them.

Mrs. Meyers shifts her recliner to the upright position. Bare toes knead carpet. Silver fillings crunch pencil lead. A delivery truck comes to a rolling stop, the driver nodding her head to the radio as she looks both ways.

“Five-zero. You would think a professional might pay attention to the rules of the road.”

An SUV slides to a halt just past the stop sign, bumper peeking over the white line.

“Six-one.” Mrs. Meyers jots it down reluctantly. “Barely,” she whispers through a mouthful of pencil. She washes it down with lukewarm, unsweetened black tea.

The school bus brakes tsss as it approaches the stop sign, and Mrs. Meyers can see it won’t slow down in time.

“Seven-one.” She marks the page, teeth bared, before the bus comes to a full and complete stop, front end poking into the lazy intersection. “Unacceptable,” she says, and reaches for the portable phone.

“911, what’s your emergency?”

“Yes, I’d like to report seven crimes.”

“Ma’am, are you in danger? This line is for emergencies.”

“Up yours! That’s what I think of your emergencies!”

Mrs. Meyers stands with one leg up on her shower chair, massaging soap between her toes. Jagged nails rake her palm. She keeps forgetting to cut them. Swaps feet. These nails are freshly trimmed, filed smoo—

Soaped up foot slips forward, her body falls backward. She lands squarely on her back, head narrowly missing the faucet. The showerhead pelts her chest, its water dripping off of her and pooling around her as it struggles to find the drain. She sleeps some, but mostly prays.

The water has run cold by the time Nancy finds her, wraps her in a beach towel, and runs to fetch the space heater.

“Did you hit your head?” Nancy runs fingers over her mother’s scalp, stares into her eyes. “Remember these things,” she snaps her fingers twice to get her mother’s attention: “shampoo, playing cards, and blankets. It’s important.”

“My back, it’s my back!”

Nancy steps out to phone the doctor, but Mrs. Meyers can hear Nancy call both of her brothers as well—she resents her daughter for it.

On the way to the doctor’s office Nancy doesn’t stop talking: “Dr. Perkins only has ten minutes for us. I hope that’s enough—have you eaten? Have a granola bar. Can you chew?” Nancy nearly runs a red light; Mrs. Meyers nearly chokes on her granola bar as they stop short.

“Do you remember the three things?” asks Nancy.

Mrs. Meyers recites them.

Nancy lets herself breathe for the first time since finding her mother.

“You’re very lucky, Beverley,” Dr. Perkins informs Mrs. Meyers over the top of her clipboard. “No broken bones, no concussion—just that nasty bruise on your spine. Ice it and take Tylenol as needed. Come see me again if there’s any pain.”

Mrs. Meyers wishes Nancy had stayed in the waiting room.

“Now,” Dr. Perkins turns to Nancy. Turns back to Mrs. Meyers. “It won’t be more than a few minutes, but I’m going to have Sandra perform a mini-mental.”

A nurse enters with a clipboard and a smile.

A city bus stops before the white line. Mrs. Meyers dozes, fully reclined, half-full mug of peppermint tea rising and falling with her breath, centimetres away from drenching her at its apex. When the portable phone rings, she flings the mug forward; it leaves a wet spot on the carpet.

“Meyerses’ residence.”

“Is this Beverley?”

“Speaking.” She spies the mug on the floor and frowns the way one would after discovering their toddler had just peed on the carpet.

“This is Dr. Perkins. I’d like for you to come in for more tests. I reviewed your mini-mental, and well, I had to contact the ministry to revoke your licence.”

“Eat shit and die.”

It’s pitch black when Nancy unlocks her car and leaves work. She speeds on empty streets, debates whether to order take-out for dinner and decides on Italian: penne alla vodka, if they have it. Pasta transports well. Does the place on Davis do take-out?

A billboard looms over the highway on-ramp. The words See Cremation Differently are superimposed over a balding, black-suited man. His face is serious, maybe even mournful, yet Nancy detects a smirk. She starts a phone call through the car’s hands-free system.

“Who’s calling at this fucking ungodly hour?” Mrs. Meyers’ words rattle the car speakers.

“It’s seven.”

“No, it—” A pause. “Quarter past seven,” she corrects.

“Has Dr. Perkins called, Mum?”

“No,” she lets it hang too long for it to be truthful.

“I’ll be over soon, Mum.”

“Okay—”

GRIFFIN SHERRIFF-CLAYTON graduated from the University of Windsor’s creative writing program in May, 2023. Currently, he is working towards his MA at Concordia in Montreal. When not studying, he enjoys brewing mead, spending time with pets, and writing. He hopes his stories are witty and poignant (although he’ll settle for either).